ANTIQUE AMERICAN FLAGS ARE OUR FOREMOST SPECIALTY

View All Antique Flags in Inventory or

choose a category from below.

View Antique Flags by Quality

Good - Antique American Flags for Beginners & Gift Giving

Better - Antique American Flags for Intermediate-Level Collectors

Best - Antique American Flags for Advanced Collectors

Masterpiece- Antique American Flags My best offerings.

View Antique Flags by Size ( in feet )

Other Categories of Antique Flags

Antique Nautical / Maritime Flags

Antique Civil War Flags

Antique Confederate Flags

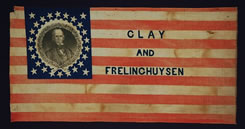

Antique Political Campaign Flags & Textiles

Antique WWII Flags

Antique Patriotic Folk Art

Antique International Flags

Antique Suffragette / Votes for Women Objects

Previously Sold Antique American Flags

Read How We Conserve and Frame Our Flags

Introduction

I feel privileged to have become the world’s largest dealer in early American Stars & Stripes. I stock at least 1,000 flags at all times, and I am always on the hunt for more

rare and beautiful examples. I take great care in both the preservation and the presentation of flags, and I encourage you to read more about the conservation processes that I use.

I employ the services of a full-time conservation staff to mount and frame both flags and other early textiles, so that they can be faithfully preserved for many years of enjoyment

and are ready to hang in your home or place of business.

I offer an unconditional guarantee of authenticity. I have dealt in early Americana for 26 years, and for the past 18 years have emphasized in 19th century textiles. In addition to flags, I also

have expertise in quilts, of which I have long been a dealer and collector, plus hooked rugs, samplers and show towels, theorems, patriotic banners, kerchiefs, and yard goods. For several years

I worked closely with Dr. Jeffrey Kenneth Kohn, the American flag consultant for Sotheby’s Auction House in New York and their internet equivalent, Sothebys.com.

While Dr. Kohn and I were working together, he catalogued both the Connelly and Mastai Collections, the two largest groups of American flags ever to be sold at public auction. But there is no substitute for learning about any manner of antique object that compares to literally handling thousands of examples, both rare and common. The education gained from being able to physically compare thousands of flags has allowed me to learn more about our nation’s symbol than any active flag dealer in the country. The information I have gleaned along the way is processed and translated into the lengthy descriptions that accompany each flag that I sell.

What’s So Interesting About Antique American Flags?

People are often surprised to learn that before 1912, lack of a specific design for the American national flag left a great deal open to interpretation and imagination. Given the level of respect our flag demands today, it is difficult to conceive that for the first 135 years of its existence, the star pattern was left up to the whims of its maker. The same was true of the number of points on the stars, not to mention all aspects of the flag’s proportions.

Circular star patterns were a favorite in the period between the Civil War (1861-65) and the 100-year anniversary of our nation’s independence in 1876. Occasionally the stars formed one great big star, termed the Great Star or sometimes the Great Flower pattern. And in rare instances they even formed letters and numbers to spell words and dates. There were all manner of arrangements of rows and columns, but the stars were positioned this way and that and seldom did they all point upward.

Because there so many interesting star configurations were designed by individuals who lacked formal training, Stars & Stripes flags of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries can be viewed as some of the greatest creations in the history of American folk art. They can be framed like paintings or draped like quilts from a supportive bar, and are interesting substitutes for both of these objects.

The flags I offer have played an important and intriguing role in American history. Unlike some other types of antiques, every flag has a story. Whether or not we know its specific history of use, within each flag there is a tale that can be unfolded concerning how it received its star count and what new state or states were involved. Sometimes there are interesting accounts of why that particular number of stars was chosen by one flag-maker and not another, or why it was quickly abandoned.

Given the liberties Americans were afforded in flag design, it is not so difficult to understand why a tasteful degree of text and graphics was almost as permissible as the stripes or stars themselves. American presidential candidates began using the red, white, and blue as a medium for printed campaign advertising as early as 1840. The first on record were made for William Henry Harrison, who served the shortest term ever as our commander-in-chief.

Though he contracted pneumonia at his inaugural speech and died just 30 days later, this beloved American figure unknowingly left behind some of the most extraordinary American flags now known to exist. Thus began a sixty-year term in American history, during which time it was perfectly acceptable for seekers of American political office to place their names, faces, and platform slogans on the much-loved symbol of our nation.

Near the end of the nineteenth century, there was a growing shift in public opinion to uphold the Stars & Stripes as a sacred object, worthy of the most scrupulous ethics regarding its use and display. Attempts were made to ban the use of the flag for advertising in 1890 and 1895, but it was not until the year 1905 that the U.S. Congress finally decreed that the use of text or portraits on official insignia of the United States would afterwards be outlawed.

Some traditions die hard, however, and this did not entirely eliminate it. Later examples survive, probably made without the respective candidates’ consent, but the turn of the new century generally marked the end of an era where politicians sought to woo their constituency with bold and whimsical versions of Old Glory.

Condition

Unlike samplers and quilts, most flags of the 18th and 19th centuries were expected to have been used outdoors. This often subjected them to wind and water damage, despite the conscious efforts of their owners. Military use introduced other hazards, of course, and was generally more strenuous. It is for these reasons that flags are not expected to be perfect. Often times they have the rips, tears, stains and foxing that reveals their age. For many of my clients, this adds significantly to their appeal, because history is apparent in the worn, weathered, and much loved symbol

of our nation. So while condition can certainly play a role in the price of an antique flag, it is far from the most important factor. A level of damage that would destroy the value of an early

quilt, for example, can be entirely inconsequential with respect to an American flag.

Types of Flags

There are basically two types of flags: sewn flags and parade flags. 19th century sewn flags are typically larger than seven feet in length. They were pieced together by hand-stitching or by machine, and were intended for use over extended periods of time. Parade flags are typically small in size, generally less than three feet, and were printed on cotton, silk, wool, and sometimes on paper. Also called hand-wavers, their purpose was intended for short term use at parades, political rallies, and other patriotic engagements. Parade flags were typically tacked or glued to a stick, intended to be waved at an event. Sewn flags were flown on staffs, poles, or masts, draped vertically on the walls of buildings, and hung from ropes, balconies or porches.

The same two kinds of flags exist today, but we seem to have found many more ways to use them. As we moved through the 20th century, the use of sewn flags became much more focused on decorative purposes, instead of fulfilling the utilitarian role of a signal to identify an American ship or structure. For this reason, modern sewn flags are generally much smaller in size than their 19th century counterparts. Today, for example, one might describe a five-foot long flag of sewn construction as “rather large”, but before 1890, a five-foot sewn flag is extraordinarily small, and a four-foot sewn flag is almost non-existent among surviving examples. Even infantry battle flags, carried by ground forces, were typically six by six-and-a-half feet, which is about the size of an average bed quilt of the same period.

After 1840 and the advent of printed flags, decorative flags were more often printed on fabric, rather than sewn. Many collectors limit themselves to printed parade flags (hand-wavers), precisely because of their small size. Many examples have beautiful star patterns and are highly sought after. We frame them very precisely in a conservation manner, most often using a frame that was made during or before the time that the flag was made. Many of the flags I use are actually earlier than the flag itself and I am especially fond of early surfaces (original patina). Parade flags typically range in size from about 3" to about 3' in length.

Many people who are new to flags shy away from printed flags, due to an uneducated notion that they are less valuable. Due to their size and extraordinary visual qualities, that is seldom the case. I set a world record at auction in 2007 by paying $83,600 for a printed, Stars & Stripes flag, so they are nothing sort of serious. Two weeks later I broke the world record for a sewn, Stars & Stripes flag at $120,700, so the disparity between the two types of flags is relatively small.

Early sewn flags (those of the 19th century and prior) typically range in size from 7' to 18' in length. Those that are 5' in length and smaller are much more scarce, and they are highly desired because they are easier to display. Smaller sewn flags can be framed in a traditional manner, or they can be stretch-mounted and displayed inside a museum quality plexiglas box. Larger flags can be hung in a variety of ways. They can be folded over onto themselves and framed to show just the stars and a portion of the stripes. They can also be folded to look like they are waving, which shortens the length in an attractive manner. And they can sometimes be displayed without frames if the light conditions are favorable, and the flag isn’t of extraordinary value, by hanging them in a manner similar to quilts or tapestries.

Terminology

Bandanna or Bandana / Kerchief — Synonymous terms for a large handkerchief. Those produced for political campaigning were printed with campaign advertising on cotton or silk.

Bleed — As a rule, parade flags are printed on one side and, because the fabric is thin and/or absorbent, the color bleeds through to the other side. This unprinted side is called the bleed and is usually lighter.

Canton / Union — With regard to an American national flag, this is the blue quadrant where the stars are located, sometimes referred to as the "Union". The term is taken from heraldry. On a traditional coat-of-arms, the shield is divided into four sections; each of these quadrants is called a "canton". Some flags have four cantons like many heraldic shields. The American national flag has one canton.

Double-Appliquéd Stars — A type of star application where a separate star is sewn on either side of the canton. This is the more common of the two methods of stitching stars to a flag. FOR RELATED TOPICS SEE single-appliquéd stars and reverse-appliquéd stars.

Field — The background of a flag; the color behind the devices or canton(s). In regard to the American national flag, the field is comprised of alternating red and white stripes.

Fly — The edge of a flag farthest away from the staff or flagpole. This term also sometimes refers to the horizontal length of a flag.

Great Star Configuration — Small stars arranged in such a manner that they form a single large star.

Grommets — Metal or whip-stitched reinforcements through which rope could be tied for flying a flag. Common thinking among military historians used to be that metal grommets did not exist during the Civil War and were therefore not used on Civil War era flags. This is a myth, however. Many Civil War-period flags have metal grommets. There are at least two patents prior to the Civil War.

These are # 5,779, issued to E.H. Penfield on Sept. 19, 1848, and # 11,108, issued to J. Allender on June 20, 1854. In fact, Penfield's 1848 patent is actually an improvement on an existing design, and therefore cannot be the earliest date.

Gussets — Square or rectangular reinforcements sewn onto in the corners of flags, to increase the amount of fabric and stitching in the places where they receive the most stress during use.

Jugate Portrait — A term used to describe a political campaign textile, especially a flag, that includes portrait images of both the presidential and vice-presidential candidate(s).

Kerchief — see Bandanna

Hand-Wavers — see Parade Flags.

Hoist — The edge of a flag nearest to the staff or flagpole. This term also sometimes refers to the vertical width of a flag.

Lineal Star Configuration: Any type of star configuration comprised of lineal rows or columns.

Medallion or Wreath Star Configuration — Technically speaking, a medallion configuration of stars can be any geometric pattern that works outward from either an open center, or a center that is comprised of a single star or a cluster of stars. Most collectors, however, reserve the term for stars that are arranged in a combination of concentric circles or circles and squares. Medallion patterns often have a center star and "outliers" in each corner.

Notched Star Configuration — A lineal star pattern where there are obvious open gaps were left so that more stars could be easily added at a later date.

Obverse — What one might think of today as the "front" side of the flag. In modern Western tradition, this is the side of the flag that is depicted when the hoist is to the observer's left. In 18th and 19th century America there was no "front" or "back". The devices, such as text and images, usually appear on only one of the two sides.

Outliers — Stars outside the main pattern, such as those in the outlying corners of a medallion or wreath pattern canton, or an oddly placed star next to a wreath or “Great Star” design.

Parade Flag — A term used by collectors for most of the types of smaller scale flags that were made by the printing of pigment or dye onto fabric or paper. Such flags were intended for relatively short-term use, to be waved at parades, political events, military reunions and other rallies. These were typically tacked or glued to a wooden staff. A somewhat out-dated, but certainly accurate, term for such flags among collectors is "hand-wavers". As a rule, most parade flags measure between 3 inches and 3 feet on the fly, though some are larger. FOR RELATED TOPICS SEE sewnflag and printed wool flag and press-dyed flags.

Portrait Flag — Political campaign flags that contain portrait images of the candidate(s).

Reverse — What one might think of today as the "back" side of the flag. In modern Western tradition, this is the side of the flag that is depicted when the hoist is to the observer's right. In 18th and 19th century America there was no "front" or "back". The devices, such as text and images, usually appear on only one of the two sides.

Reverse-Appliquéd Stars — A type of star application where the shapes of stars are clipped from within a length of fabric, then that fabric is laid over a background so that it shows through the star-shaped holes. In the case of a Stars & Stripes, star-shaped forms are cut from within a rectangular length of blue fabric, which is then laid over a white ground. The white shows through to become the stars. The seamstress would then sew around the stars to join the two lengths of fabric. This is a very uncommon method of construction. FOR RELATED TOPICS SEE single-appliquéd stars and double-appliquéd stars.

Printed Wool / Press-Dyed Flags —Flags manufactured by press-dying on wool bunting. This was a resist-dye process, first patented in the U.S. for the manufacture of flags in 1848. It never became a popular method of flag production in America, where it seems to have been abandoned after 1876, but was pursued with greater intensity and for a longer period of time in Great Britain.

Some parade flags were printed or press-dyed on wool. Others were printed on wool and cotton blended fabric. Some larger varieties of press-dyed and printed wool flags needed to be pieced in several sections. Some flags have printed or press-dyed wool cantons, but have stripe fields that are pieced-and-sewn from individual lengths of fabric. FOR RELATED TOPICS SEE sewn flags and parade flags.

Random Star Configuration — A configuration of stars without rows, columns, or any apparent pattern.

Rectilinear Star Configuration — Lineal rows of stars arranged so that they line up both horizontally and vertically.

Reverse-Appliquéd Stars — A construction method seldom seen in American national flags. Here the canton is made by taking a length of blue fabric and cutting out star shapes. This is appliquéd over a white background to create the stars. SEE ALSO double-appliquéd

stars and single-appliquéd stars.

Reverse / Backwards Mount — A mount where the canton of an American national flag is placed in the upper right-hand corner instead of the upper left.

According to modern flag ethics and the U.S. Flag Code, the canton of an American national flag should always be displayed in the upper left. During the 19th century, however, the same flag ethics that we have today did not exist, so this seemingly backwards positioning was just as acceptable. For this and other reasons, backwards mounts are very much acceptable amoug the collectors of antique flags.

A backwards display of an antique Stars & Stripes is sometimes necessary because:

(a) Some flags were one-sided, particularly in the case of homemade examples.

(b) Some flags have lettering and/or images in the canton or stripes that are only visible on one side.

(c) Some flags are stronger or more visually interesting on the then they are on the obverse.

Scattered Star Positioning — Stars on a flag that may be arranged in any pattern, but which are individually aligned in a various directions on their vertical axis.

Sewn Flag —A flag made by the piecing, stitching, appliqué and/or embroidery of any combination of fabrics.

Walter Hunt built the first crank-operated American sewing machine in 1833-34. Elias Howe, of Massachusetts, completed his first mechanized sewing machine prototype in 1844, and it was issued an American patent in 1846. Because of problems marketing his invention, Howe went to London to further develop the machine. Treadle sewing machines were first mass-produced in 1855 by American, Issac Singer.

By the time of the Civil War, sewing machines were being used on roughly 60 – 70% of American national flags. By the Centennial, the treadle machine was used on almost all stripes, but the stars were typically still hand-appliquéd. By the Spanish American War (1898), hand-sewing on American national flags had all but vanished.

Many 18th and 19th century military flags actually had painted stars. These were often gilt-painted in gold or silver, but are sometimes white on homemade flags. White pigment was aslo used on some commercially-made flags produced during the 1st half of the 20th century.

FOR RELATED TOPICS SEE parade flags and printed wool / press-dyed flags.

Single-appliquéd Stars —A type of star application where only one piece of fabric is used to make a star that is visible on both sides of the flag. On a stars and stripes, this is accomplished by making star-shaped cutouts in the blue material. A white star is then appliquéd over top of the star shaped hole. On the reverse side, the rough cut fabric is rolled over and hemmed so that the white star shows neatly through the hole. Single appliquéd stars are genera double-appliquéd stars and reverse-appliquéd stars.

Word Flag — A term traditionally used by the collectors of political campaign flags for flags that have text, such as names and slogans, but no portrait images of the candidate(s).

Vertical Mount / Correct Vertical Position — Manner of hanging a flag vertically instead of horizontally. After approximately the year 1900, the proper position for the canton of the flag is always in the upper left corner, whether the flag is horizontal or vertical. During the 19th century, however, the same flag ethics that we have today did not exist.

Wreath or Medallion Configuration — stars arranged in concentric circles, often with a center star and "outlier" stars in each corner.

| Jeff R. Bridgman Antiques, Inc • Historic York County, Pennsylvania • Tel. 717-502-1281 or 717-676-0545 • info@jeffbridgman.com All images and Text © Jeff Bridgman 2001 - 2021 |