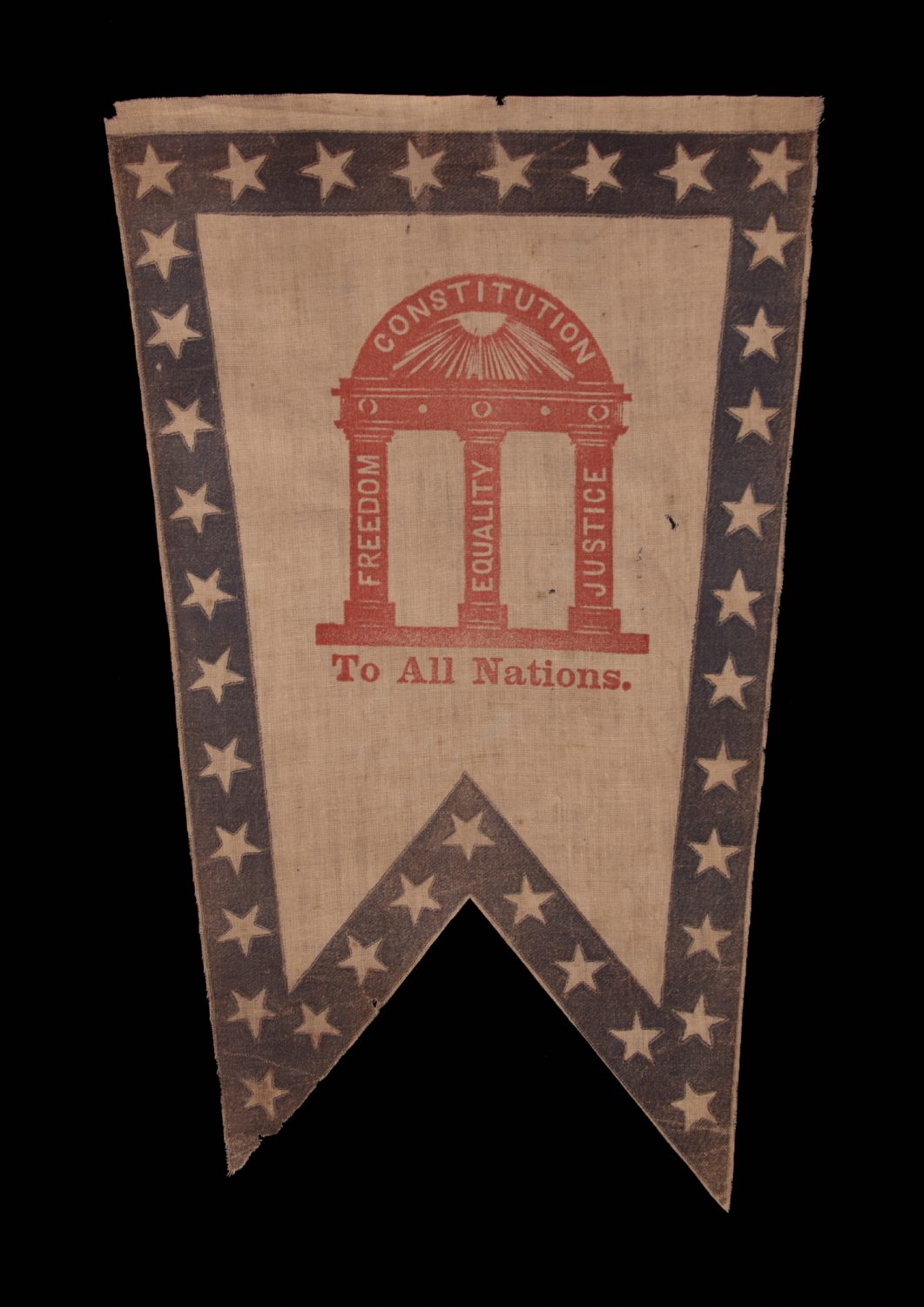

| SWALLOW-TAILED PARADE FLAG / BANNER WITH A 37 STAR BORDER AND A CURIOUS ADAPTATION OF THE ARCH FROM THE GEORGIA STATE SEAL WITH THE WORDS “FREEDOM, EQUALITY, AND JUSTICE,” FOLLOWED BY “TO ALL NATIONS,” LIKELY MADE FOR THE 1876 CENTENNIAL INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION IN PHILADELPHIA; OF A GENERAL TYPE KNOWN TO HAVE BEEN PRODUCED BY THE AMERICAN FLAG COMPANY OF NEW YORK |

|

| Web ID: | pat-836 |

| Available: | In Stock |

| Frame Size (H x L): | Approx. 22" x 17" |

| Flag Size (H x L): | 12.75" x 8" |

| Description: | |

| Early American parade flag / banner, printed on coarse cotton, with a white ground and a narrow blue border that contains 37 white stars, evenly dispersed. In the center, block-printed in red pigment, is a curios modification of the device on the seal of the State of Georgia. Formally adopted in 1799, the actual format—still in use today—consists of a broad arch, with the word “Constitution” emblazoned upon it, on a header supported by three pillars. The reference is to the state’s own constitution, with columns to represent the three branches of government: legislative, judicial, and executive, wrapped in billowing streamers that read: “Wisdom, Justice, and Moderation.” The device that appears on this parade flag is a close variant, with the verbiage changed to instead display the principles of “Freedom, Equality, and Justice,” in this case printed directly on the columns, . Though I have researched the alteration extensively, and can find no period explanation or source image, the verbiage almost certainly reflects post-Civil War Georgia, in the wake of emancipation and reconstruction. I suspect that there survives, somewhere, a cartoon or sketch that substituted these words, perhaps published in a newspaper, or a magazine such as that of Frank Leslie or Harper’s Weekly. The words “To All Nations” is more telling. This reflects obvious purpose for display at a World’s Fairs. The first of these to occur in America, known as the Centennial International Exhibition, took place in Philadelphia in 1876. Held in honor of our nation’s 100th anniversary of independence, this 6-month event occurred with such resounding success that it brought about many others in the last quarter of the 19th century, as well as the opening decades of the 20th. Sometimes banners of this sort displayed a star count that reflects the number of states in the Union at the time that the textile was produced, and sometimes not. Here the count of 37 stars is relevant. Though Colorado joined the Union as the 38th state on August 1st, 1876, stars were not officially added until the 4th of July following a state's addition (per the Third Flag Act of 1818). For this reason, 37 remained the official star count until July 4th, 1877. Though flag-making was a competitive venture, in which no one seems to have cared what was official, adding new states instantaneously on their acceptance, if not even beforehand, in hopeful anticipation, a number of patriotic textiles from the Centennial Exposition survive with 37 star borders, such as this one, likely because some designs were produced well in advance. This basic type of banner is known to have been produced by the American Flag Company in New York City.* Similar designs were available from various flag-makers, however, who copied one-another in competition for the same clientele of political, fraternal, and veteran’s organizations, World’s Fairs, political conventions, celebrations of July 4th and all manner of patriotic events. Swallowtailed banners, some with straight profiles and others tapered like the burgees flown on ships, were offered as templates used to feature various text and images within. These were usually available with an array of standardized elements, such as presidents, dates of anniversaries (such as “1776-1876”), names of fraternal groups, Civil War corps badges, and a myriad of state seals. They could also be special ordered with whatever one desired. A banner in the same style, though larger [at 17” x 23.5” instead of 8” x 12.75”], made for the centennial, with an image of the Liberty Bell and displaying 37 stars, is documented in “Threads of History: Americana Recorded on Cloth, 1775 to the Present”, by Herbert Ridgeway Collins, (Smithsonian Press, 1979), as item 374, on p. 187. Collins formerly served as the Smithsonian’s Curator of Political History. It is of interest to note that a straight-sided banner in similar format, with a portrait image of Abraham Lincoln, and presumably a bit larger, also appears in the Collins text as plate 40 on p. 21. Shown hanging from a building in a street scene, he describes this as having been “…taken in the 1880s in front of a general store on Main Street in Richmond, decked out by its Negro proprietor to commemorate the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation January 1, 1863, known and observed as Liberation Day, or the former slaves’ day of independence.” The words “Liberty” and “Equality” on this pennant suggest similar use. The topic of equal citizenship and the attainment of business ownership, academic achievement, etc., received attention at World’s fair events. The most notable of these during the 19th century, known as the Cotton States & International Exhibition, actually took place in Georgia in 1895. Held in Atlanta, this incorporated a huge exhibit space called “Negro Building,” which, according to the fair’s official guide, was “140 feet in width and 270 feet in length.” The publication goes on to state the following: “This is the only building ever erected at an exposition for the sole purpose of demonstrating the progress of the negro race in the arts of civilization. The exhibit covers a period of over 50 years period the building has a central tower 30 feet at the base by 70 feet in height… The main entrance is flanked by two smaller power is 40 feet in height, and there are in addition 4 corner towers of the same height. The main floor has an area of 23,998 feet. The building is constructed of wood, iron, and glass and was erected at a cost of $9,922. The outer covering is of shingles. The color is Gray, white, and green and harmony with the other structures. Glass has been used liberally and no building on the ground is better lighted. Handsome medallions in terracotta and staff over the entrances, pediments ornamented with the same material and relief, and the breaking up of the broad stretches of the facade with towers produce a decidedly agreeable architectural effect. The attractive exterior is enhanced by figures in ornamental staff work in the pediment contrasting the condition of the negro 50 years ago with the present day. On one side is seeing a picture of the primitive log cabin in the face of an old negro mammy, her head covered with the characteristic bandanna. On the other side in contradistinction to this view appears the face of a representative negro of this day and generation, the late Frederick Douglass, who represented his people in important positions of honor and trust. The many splendid exhibits shown in their own building demonstrate the fact that they have availed themselves of the opportunities offered and show a constantly increasing advancement along the line of moral, intellectual and material progress. The negroes throughout the South have great interest in this building. The contractors and laborers employed were all of the colored race.” I would be more likely to suggest an 1895 date on a banner without a 37 star border. Though an 1875-1876 print block may have been employed to create a banner sold in the 1890’s – few people are likely to have counted the stars and many such banners displayed a number that had nothing to do with the number of states, such as 70 stars, meant to simply be patriotic, presumably without any other care but for their artistic composition, those I know to use true star counts tend to be period to the date with which they correspond. For some reason, both copper plate engravings and print blocks seem to have been discarded fairly promptly. The number of flags and kerchiefs that use different print blocks or plates to produce nearly identical textiles -- even in the mid-19th century where waste not tolerated like it is today, and access to resources was far more limited -- is simply remarkable. Whatever the case may be with regard to the origin of this exact banner, the design evidently gained widespread admiration, possibly having been liked by Union Army veterans, whose reunions hit full swing in the 1890’s – 19-teens. What began with a modification of Georgia’s seal evidently became a standard image for these swallowtailed banners in flag-makers’ catalogues. Illustrations of the same basic style, minus the “To All Nations.” text, appear in the 1901 catalogue (No. 21) of the C.H. Koster Co. of New York, as well as that of a 1907-1911 era catalogue (No. 16) of the aforementioned American Flag Company, also of that city.* Lack of the verbiage pertinent to Worlds’ Fairs would have been more appropriate for Civil War veterans and celebrations of emancipation. * Not to be confused with another firm by the same name in Easton, Pennsylvania. Mounting: The flag was mounted and framed by us in-house. We take great care in the mounting and preservation of flags and related textiles and have preserved thousands of examples. For 25 years we have maintained our own textile conservation department, led by a master’s degree level graduate from one of the nation’s top university programs. The background is 100% cotton twill, black in color, that has been washed and treated for colorfastness. Framing behind U.V. protective glazing is included. Condition: There is modest to moderate fading and there is minor to modest pigment loss in the blue portion of the printing. A tear on the lower left-hand tip was repaired with a tiny bit of archival adhesive (invisible to the naked eye). There are tiny tack holes along the top, where the flag was once affixed to a split wooden staff, and there are a couple of tiny holes elsewhere. There is extremely minor soiling. Many of my clients prefer early flags to show their age and history of use. |

|

| Video: | |

| Collector Level: | Intermediate-Level Collectors and Special Gifts |

| Flag Type: | Parade flag |

| Star Count: | |

| Earliest Date of Origin: | 1876 |

| Latest Date of Origin: | 1895 |

| State/Affiliation: | Georgia |

| War Association: | 1861-1865 Civil War |

| Price: | Please call (717) 676-0545 or (717) 502-1281 |

| E-mail: | info@jeffbridgman.com |

|

|